Active Learning: Overview and Introduction

Overview and Introduction: The WHAT and WHO

*Please note that this Quick-Reference Guide is longer than other guides as it provides an overview of Active Learning and contains more content, links, and research than most other QRGs available on the FSE L&T Hub site.

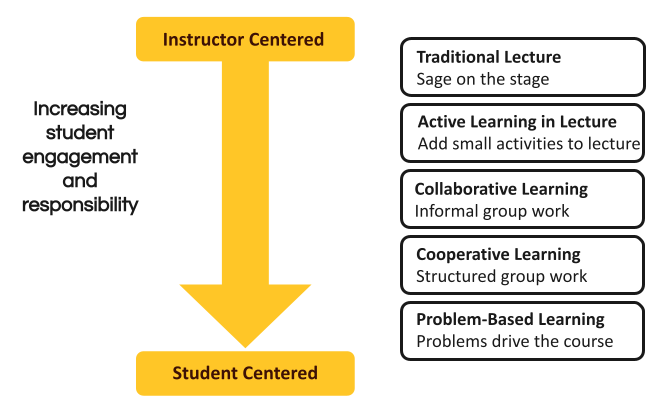

Active Learning is a term used to describe instructional methods that increase student involvement and engagement in the learning process. In contrast to traditional instructor-centered delivery, where there is a passive transmission of facts and ideas through lectures, active learning incorporates a variety of instructional strategies that purposefully shift the learning environment to be more student-centered, and focused on what the student will be ‘doing’ during the learning process.

Active Learning is rooted in the educational theory of Constructivism, which centers on students ‘constructing’ their understanding of a concept and integrating that new information with pre-existing knowledge. Active Learning may include reading, writing, discussing, and problem-solving as well as the incorporation of hands-on activities and reflection-based activities, among others. Together, these approaches seek to engage learners in higher-order thinking, resulting in greater retention and depth of understanding of content.

What about a lecture?

Using active learning does not mean you have to abandon lectures. Instead, visualize active learning on a continuum ranging from simple pauses in lecture that allow for student questions and reflection, to more complex cooperative and problem-based projects.

Active Learning works well in nearly every type of course, and with all types of learners. As detailed in the Implementation and Timing section below, research suggests that students experience increased content comprehension, retention, and metacognitive skills in STEM courses that use active learning, making it an excellent strategy to implement in both large and small classes, particularly in courses with challenging content. With a little practice and planning, all types of instructors can successfully implement a variation of active learning that works best for their course and their students. more active as they interact with peers and the course content. Students of all years will benefit from the use of active learning strategies in an online course.

Implementation and Timing: The WHEN, WHERE, and HOW

There is no ‘right time’ to use active learning. It can be implemented at the beginning of a course as a way to break the ice and encourage student-to-student interaction, during lecture-style classes as a way to improve student reflection, engagement, and attentiveness, or at the end of the course as a strategy for review before an exam. While there is no right answer to when active learning should be used, it may be helpful to set the expectation of active participation from the beginning of the course. Suddenly switching from a lecture-only course to one filled with activities halfway through the course may be confusing and frustrating for students.

Active Learning is a good fit for a variety of courses and settings and can be used both in and ‘out’ of the classroom. When designing a course, consider the best use of face-to-face or synchronous time. Research suggests that students can easily complete lower-level readings or activities (such as watching a short pre-recorded lecture) ahead of the class session, freeing more time in class for interaction, problem-solving, and active learning. If you’re struggling with where in your course to include active learning, start by identifying a class session that includes a lot of lecture time, or one that has concepts that students find particularly challenging. Active learning can improve these sessions by breaking up long lectures to re-engage students as well as providing them with time to process and reflect on the new information being shared.

*While this guide focuses primarily on in-class strategies, activities like Canvas discussion posts and after-class group work are examples of out-of-class activities that leverage the value of active learning and student engagement. For additional ideas on online active learning, check out the ASU Teach Online website.

Common Faculty Concerns

According to Felder and Brent (2016), the five most common instructor concerns about Active Learning include:

- Covering content in the syllabus

- Spending lots of time on designing activities

- Noise levels and time wasted getting students back on track

- Some students will refuse to work in groups

- Students will complain/student ratings of course will fall

These are legitimate concerns when introducing active learning. Fortunately, there are a variety of strategies that can help mitigate these challenges. Here are a few suggestions to make the active learning transition progress more smoothly.

Plan for Implementation: Start small, begin early, and choose low-risk activities.

- Start small. Choose strategies that take little to no planning as well as those that don’t require a large in-class time investment. Remember, activities don’t need to be long or complicated to be effective.

- Ensure early activities provide a low barrier to success. Students may initially be apprehensive about working in groups, especially if they do not know other students in the class, so consider playing an active role in the first few activities, introducing students, and speaking with students as they work in small groups. Make sure early activities are relatively simple and that the directions for the activity are clear.

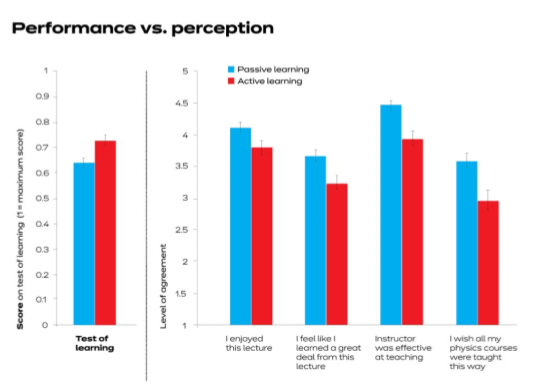

- Share the WHY. Explain to students why you are incorporating these activities. You may wish to share with students that these strategies have been shown to improve content comprehension, retention, and metacognitive skills. Keep in mind that students often rate non-lecture activities lower despite the fact that they actually learn more in active-learning classrooms (Deslauriers et al., 2019), so sharing the rationale and research about active learning can be an important (and often overlooked) step in the implementation process.

Note: Adapted from Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom by Deslauriers et al., 2019

Consider the needs of the specific class

- Identify a topic or activity that fits well with the course. Is there a topic students find particularly difficult in this course? If so, is there an active learning strategy that can help improve student comprehension of the concept? Perhaps students need additional opportunities to review the content or to apply the concept in a new context. Students may benefit from a short activity that helps them connect one concept to another or one that links a topic from class to a real-world problem. Active Learning strategies can be helpful for these types of challenges and can also be useful in uncovering student misconceptions and encouraging student reflection.

- Leverage backward design. As you work through this process for your course, consider using a ‘backward design’ approach where you 1) begin by identifying the student learning goals and objectives, 2) consider the assessment that will be used to determine when a student has mastered those goals, and then 3) choose active learning strategies that will help students progress from their current level of understanding to the desired endpoint.

Here are some additional tips on how to avoid common mistakes when implementing active learning:

| Common Mistake | How to Avoid the Mistake |

|---|---|

| Plunging into active learning with no explanation | Explain what you’re going to do, how it will work, and why it is in the student’s best interest |

| Expecting that all students will eagerly get into groups the first time you ask them to | Be proactive about helping students with the first few group activities |

| Making activities trivial | Make active learning tasks challenging enough to justify the time it takes to do them |

| Making activities too long | Keep most activities short and focused (five seconds to three minutes). Break large problems into smaller chunks |

| Calling for volunteers after every activity | After some activities, call randomly on individuals or groups to report out (reporting out is time-consuming and does not need to be done for every activity) |

| Falling into predictable routine | Vary the formats and lengths of activities and the intervals between them |

Assess the strategy: Reflect, review, and assess

- Reflect. While the activity is still fresh in your mind, reflect on any challenges that students experienced. How could this be improved in future iterations? Are there any changes that would make the activity easier or less stressful for you? Could you leverage TAs or lead students to help facilitate future activities?

- Review. Consider gathering student feedback on the activity. As discussed above, students often rate any activities that stray from the traditional lecture format lower, so make sure to ask probing and specific questions.

- Assess. Did the activity improve student comprehension of the topic? What updates or changes can you make to this activity, or similar future activities, based on the data from this round of implementation?

Rationale and Research: The WHY

Active learning, rooted in the theory of constructivism, champions the idea that students should actively participate in the learning process. Active Learning decentralizes the learning from the instructor and supports them in presenting information more effectively. Active Learning also better prepares students for the current workplace, encouraging them to develop Entrepreneurial Mindset skills of curiosity, making connections, and creating value in their learning.

Active Learning:

- Shifts focus from what the instructor should deliver to what the students should be able to do

- Motivates students to be prepared for class, having assimilated material and be ready to use it

- Engages students more fully in the learning process because they have to do something

- Results in better retention and higher-level learning

Active learning improves student achievement (retention and comprehension) by allowing students the opportunity to practice and apply newly acquired skills, reinforces key concepts, builds in metacognition, and provides more frequent and immediate feedback to students on their level of content comprehension. It also creates more opportunities for social and collaborative interaction, two factors that are particularly important for underrepresented students in STEM disciplines (Crescente & Lee, 2011; DeWitt et al., 2014).

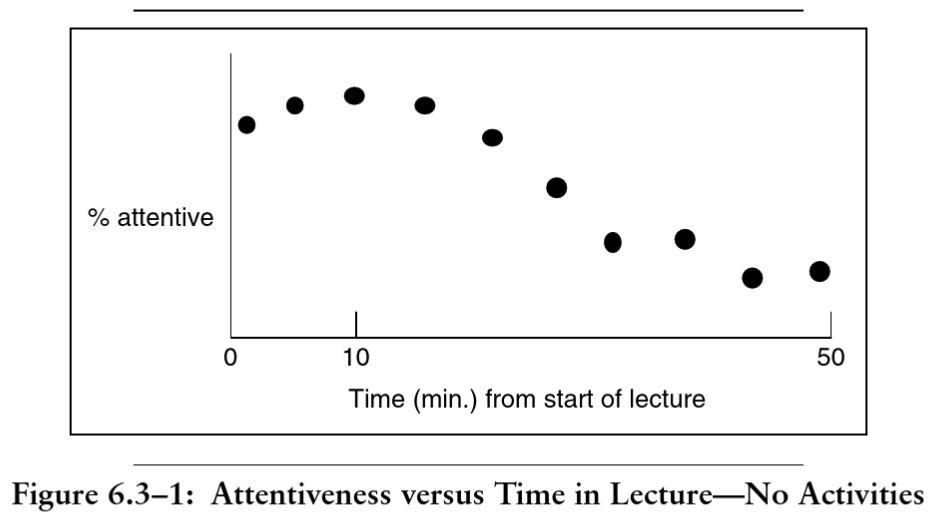

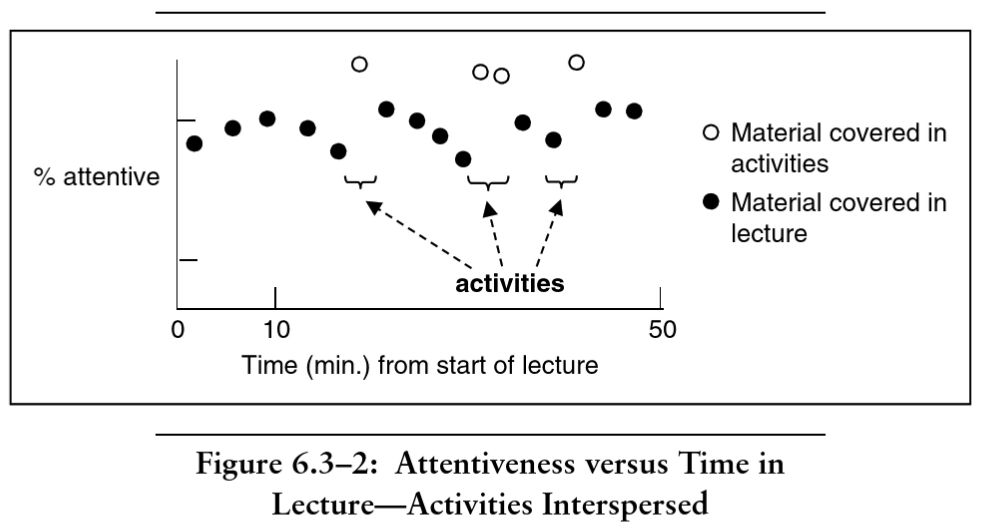

In addition to the benefits listed above, Felder and Brent (2016) remind us that learning requires attentiveness. Human attention spans are short and it is challenging for students to remain engaged while they are passive. Consider the typical student attention span during a standard lecture class. Attention begins to wane around the ten-minute mark in the lecture. Simple activities such as a reflective question or Think-Pair-Share re-engage students and improve their attention span (and subsequent comprehension) throughout the class session.

Note: Adapted from Teaching and Learning STEM, by Felder & Brent, 2016, p 118.

Does Active Learning Work?

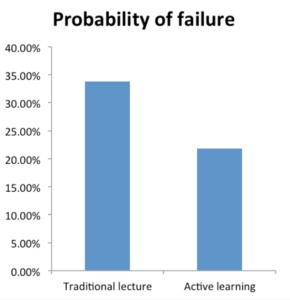

The evidence that active learning is more effective than traditional instructor-centered models is robust and backed by nearly four decades of research. In their meta-analysis of 225 studies comparing active learning and lecture in STEM disciplines Freeman et al. (2014) found that students in active learning courses demonstrated improved attitudes towards learning and STEM and scored half a standard deviation higher on identical or equivalent examinations, concept inventories, and other assessments than those enrolled in lecture-style sections. Furthermore, students in active learning classrooms were 33% less likely to fail courses than their peers in traditional lecture-style courses. These results align with hundreds of studies, including earlier large-scale reviews of research (e.g., Hake, 1998; Prince, 2004; Springer et al., 1999; Wieman, 2014).

Note: Adapted from Active Learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics, by Freeman et al., 2014

In summary, lecturing nonstop almost guarantees most content will not be retained in long-term memories. Research has demonstrated conclusively that a combination of lecturing and activity promotes learning much more effectively than lecturing alone. With that in mind, consider the following:

- How could you ensure this happens more consistently?

- How are you currently providing (or planning to provide) opportunities for students to actively participate in your course?

- Is there a way you could provide more of these opportunities?

Additional Resources and References

Interested in learning more? Here are additional readings on active learning topics with citations and links to articles referenced in this document.

University of Michigan Introduction to Active Learning