Rubrics

Overview and Introduction: The WHAT and WHO

Overview and Introduction: The WHAT and WHO

Rubrics are a best practice for letting students know the expectations of all deliverables of a course. While the design and use of rubrics vary, in its simplest form a rubric is a matrix that explicitly lists evaluation criteria and standards [1], each associated with a detailed description and score. An effective rubric takes time to design, but then speeds up and improves grading [2].

Rubrics are used in grading scheme:

- When the student’s level of performance depends on expert judgment

- For assessing open-ended problems, projects, and professional deliverables

- For deliverables that depend on higher levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy

- In the assessment of professional skills, such as Entrepreneurial Mindset

Grading rubrics can be implemented in all course formats (i.e. face-to-face, hybrid, online), content areas, and various types of assignments (e.g., discussions, papers, presentations) but the effectiveness of a rubric depends on how well it is written [2].

Implementation and Timing: The WHEN, WHERE, and HOW

Implementation and Timing: The WHEN, WHERE, and HOW

Rubrics should be used early and throughout assignments in your course. This will help you establish academic guidelines on what is expected from the students on discussions, assignments, projects, etc. It’s best to have rubrics present in an assignment before the student attempts it, so they have an understanding of the expectations on that assignment.

Rubrics are created when connecting the course learning objectives to the assessments. In a backward design approach to course development, rubrics are created early in the course design process to help connect the desired learning outcomes and assessments. The development of an effective rubric may take multiple passes before you have the criteria fully figured out. A rubric improves each time you use it for grading. Individual and collective student responses provide clues as to how to adjust rubric criteria and/or instruction to make students more able to achieve target competencies. These adjustments might be frustrating initially, but they reflect an underlying need that might not be evident without rubrics. When the rubric criteria are specific and observable, quality of open-ended deliverables improves, grading is streamlined and more consistent, and there should be less student questioning of grades [2].

Rubrics can be included on any assignment in which students will be graded. Rubrics should be specific to each assignment when possible, avoiding the use of a “global” version that spans all assignments within the course. Due to the unique nature of the individual assignment, different rubrics for each assignment/quiz is preferred. However, maintaining consistency across each assignment “type” can make rubric development easier as you can copy and paste parts that are globally applicable.

Rubrics can be created directly inside of Canvas and associated with a scorable assignment. Learn more on how to create a rubric in Canvas here.

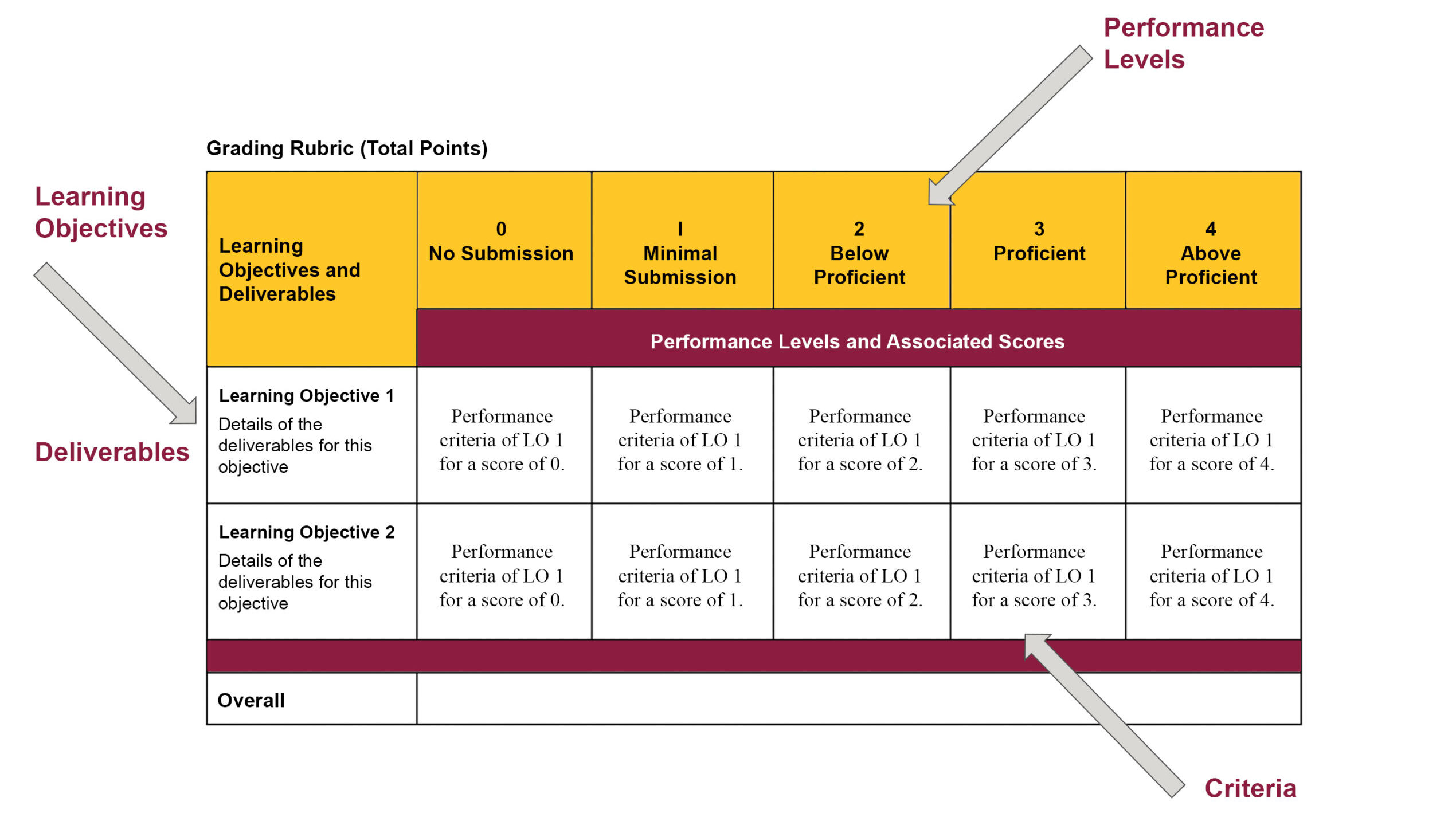

A well designed rubric has four basic parts:

- Learning Objectives (Student Outcomes): The learning objectives detail what the learner should be able to do by the end of the experience. Within a course, there are a number of learning objectives and all assignments within the course should be assessing the learners ability to these things. Learning objectives are brief statements and are usually covered and assessed multiple times within a course.

- Deliverable(s): The deliverables are more specific to the assignment being assessed. The deliverables detail how the student can demonstrate their ability to achieve a learning objective. The deliverables are targeted to the specific assignment being assessed.

- Performance Levels: Also known as grades. The performance level communicates to the student how well they met the criteria of a learning objective/deliverable on a specific assignment. Performance levels can be set values or ranges and should give some explanation regarding the expected score for proficiency.

- Criteria: The criteria are the most important part of any rubric. The criteria are used to determine how well a student demonstrated the ability to accomplish the deliverable.

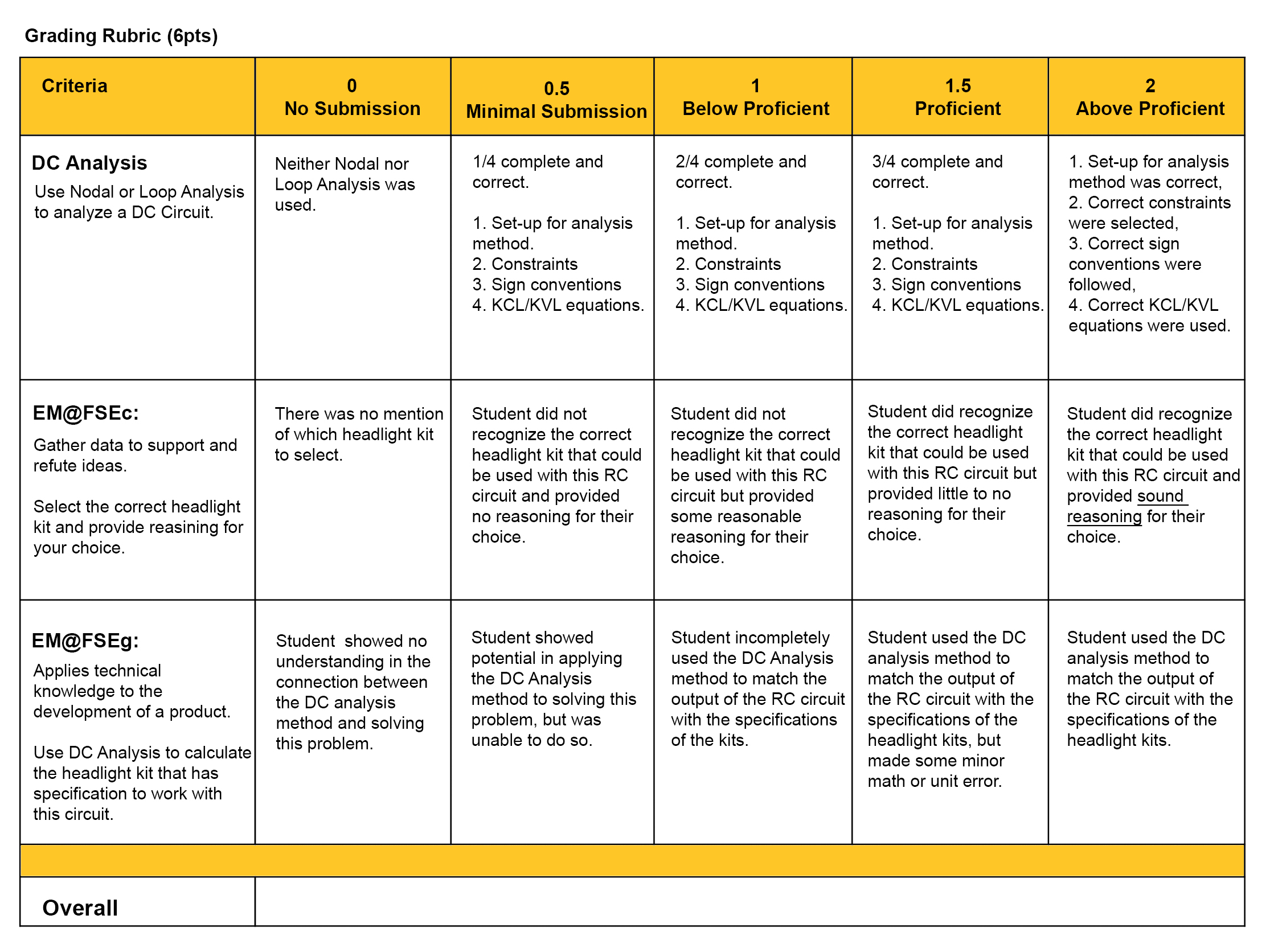

The example is one form of a grading rubric. As long as the four basic parts are included, the rubric can have different configurations. In the figure below is a more specific example from an Electrical Engineering course:

The genius of excellent rubric design is in creating criteria that are specific, observable, and reflective of the learning objectives. This can be more challenging than it sounds.

- Criteria are specific and observable. Individually and collectively, criteria directs students on how to go about creating a deliverable. It is important to consider whether each criterion has been taught and whether you are using vocabulary in the criteria that has been defined within the course.

- Criteria provide direct evidence of learning objectives/student outcomes. Individually and collectively, criteria provide direct evidence of competence in the Learning Objective(s). Therefore, be sure to confirm the link between the criteria and the target Learning Objective. It is important to consider:

-

- Is this criterion evidence of the target learning objective?

- If students score proficient or above proficient, will they have demonstrated competence in the target learning objective?

- Do the criteria listed cover all requirements to demonstrate the ability to accomplish the deliverable?

- Are there more than 5 criteria in one deliverable? If so, can you reduce the number of criteria or should the deliverable be split? There should only be one learning objective per set of criteria..

- Criteria are designed for efficient grading. Inconsistent grading methods can have a considerable impact on student success. [3] Using rubrics effectively can reduce inconsistencies even when grading is completed by multiple people (including instructors, TAs, and graders). Some techniques to improve grading efficiency using a rubric include:

- Fewer the performance levels – the more performance levels you include, the more variation in scores

- Create a rubric for each performance level – it clarifies expectations and saves time with grading and student complaints.

- Having a point range, instead of a single value, at any performance level, can make grading easier. If “proficient” is between 2-3 points, you have latitude in scoring that avoids having to make difficult decisions about whether a deliverable falls under, at, or above proficient.

- Don’t include more than 5 criteria for any performance level.

- Grading can be holistic (all criteria overall), or analytical (each criterion is graded, scores summed or averaged). Generally, grading might be faster when criteria are assessed holistically. However, when one or more criteria are closed-ended answers, analytical grading might be faster.

- Structure deliverables so that criteria for each objective are easy to find. Consider using PPT templates, with a required format for each slide or papers with structured outlines, for example.

Implementation Steps:

1. Review the learning objectives of the task. The learning objectives are the fundamental metrics for rubrics. Before starting a rubric it is always good to go back to the objectives and see if the activity will promote learning toward the objective.

2. Identify which skills/competencies are needed in the task. Think of the learning objective as the larger goal. Then, which skills a student should have to accomplish the activity?

💡 Start with your highest proficiency level and work backwards. Define criteria in accordance with the skills/competencies evaluated in each task.

3. Define criteria in accordance with the skills/competencies evaluated in each task.

4. Define what are the learning outcomes for each skill/competency assessed.

5. Establish the weighting of the task on the course grade: Although feedback may be more valuable than course grade, it is still an important element of students’ motivation.

6. Establish the weighting by considering how important the task is for the learning outcome and how much time students will invest doing it. Define level of performance for each skill and provide examples of each level: scoring rubrics usually present 3-5 levels of performance. For each level of performance provide clear concrete examples. It helps students to better understand how they are being assessed.

💡 Having criteria indicated at each performance level reduces time dealing with student complaints about grades.

7. Review and validate the rubric with the teaching team/TAs. Consider revising and reworking the rubric, reflecting after each use to ensure it continues to be effective and efficient for grading and feedback. (after the assessment, semester, etc.)

A rubric should not give away the answer to the problems you’ve posed or the challenges you’ve set out. An effective rubric outlines a process or critical considerations engineers use to solve problems. Rubrics level the playing field. “A” students will discern or intuit the underlying processes. “B” and “C” students may need to be taught explicitly. Rubrics provide sign posts for all students.

💡 Students may believe that open-ended items are entirely subjective, but they are not. Professionals (including faculty) internalize standards of acceptable practice based on disciplinary norms and conventions. Your assessment isn’t just your opinion—it is representative of standards in the field, to which you are socializing students.

Rationale and Research: The WHY

Rationale and Research: The WHY

The benefits of rubrics are that they:

- Provide clear targets that help students complete challenging tasks successfully.

- Provide clear targets to faculty regarding what to teach in order for students to develop competence in core learning objectives.

- Promote consistency in grading student deliverables. [4]

- Promote better quality student deliverables.

- Speed up grading, especially in Canvas combined with SpeedGrader.

Creating rubrics at all levels has the advantage of clarifying expectations for each deliverable, as well as creating clear benchmarks for students. Rubrics are also useful tools in maintaining consistency between graders and sections of a course, which can be helpful in larger courses, or courses where graders assist in the evaluation process.

Additional Resources and References

Additional Resources and References

Interested in learning more? Here are citations and links to articles referenced in this document.

Acknowledgment: This work acknowledges the 2020 presentation on the anatomy of a rubric, by Gary Lichtenstein as part of the ASU Kern Grant Robust Entrepreneurial Mindset Leaders (REML) project.

[1] B. Walvoord and V. J. Anderson, Effective grading: A tool for learning and assessment in college {the jossey-bass higher and adult education series ; 2nd ed.}. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. (US), 2009.

[2] W. J. Popham, What’s wrong-and what’s right-with rubrics. Educational Leadership, 55, 1997, pp. 72-75.

[3] W. B. Armstrong, The association among student success in courses, placement test scores, student

background data, and instructor grading practices. Community Coll. J. Res. Pract. 24, 681–695 (2000).

[4] N. M. Hicks and H. A. Diefes-Dux, Grader Consistency in using Standards-based Rubrics Paper presented at 2017 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Columbus, Ohio. 10.18260/1-2–28416